Embodying the Museum: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Connections and 82nd & Fifth

Teresa Lai, USA, Christopher Noey, USA

Abstract

Two recent collection-focused online initiatives from The Metropolitan Museum of Art use the digital space to redefine the Met's culture and voice for a global audience: Connections and 82nd & Fifth. Both features were in-house productions, creative experiments limited to a single calendar year. Not only did they offer new intellectual bridges to the collections for the Met’s audiences, but the process of making them also saw an internal transformation of the institution itself. Connections and 82nd & Fifth's series producer and director propose to discuss the philosophical thinking and practical processes behind these two projects that have broader implications for other museums navigating the digital space.

Keywords: Connections, 82nd & Fifth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1. Introduction

As producer and director of two recent collection-focused online initiatives from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Connections (2011) and 82nd & Fifth (2013), we discuss in this paper the philosophical thinking and practical processes behind two projects that redefined and redirected the Met’s culture and voice for a global audience. These may have broader implications for museums navigating the digital space.

Both features were in-house productions and creative experiments limited to a single calendar year. Not only did they offer new intellectual bridges to the collections for the Met’s audiences, but the process of making them also saw an internal transformation of the institution itself.

Each year at the Met, six million visitors come through our doors on Fifth Avenue in New York City, and we receive fifty million visits to our website. Our goals online used to be predominantly about getting people to the museum, and about giving Web visitors authoritative facts. Like any responsible museum website, we provide collection records on works of art in the museum: at this time, four hundred thousand object records and growing. Scholars, and even the general public, make great use of the website’s collection database. Their consistent, scholarly texts, accompanied for the most part by well-lit photographs, present works of art in a thorough but mechanical fashion. In our quest to responsibly publish our holdings for the public, have we lost sight of the power that works of art have to move us emotionally, engage us deeply, and take us out of our ordinary lives?

This paper explains some of the key questions we continually ask ourselves in the creation of online initiatives focused on our permanent collection. They are:

- What is the focus on the collection?

- What is the definition of the expert voice?

- What is the appeal to the public?

- What does this project do for the institution?

Before we discuss the focus of this paper, the projects Connections and 82nd & Fifth, to give some background we need to briefly introduce a project the Met initiated more than ten years ago, the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. As a suite of three online initiatives on the Met’s collection, the Timeline is our academic staff’s vision of the history of world art seen through our collection; Connections is one hundred staff members’ personal, non-art historical perspective on our collection; and 82nd & Fifth is one hundred curators’ rumination on one hundred works of art that transformed the way they see the world.

2. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History was the Met’s attempt, beginning in 2000, to create a website on the permanent collection that would realize the institutional vision in introducing the collection to its Web audience. It is a resource that is being developed on an ongoing basis. Our original goal was, and is, to identify from the collection works that are deemed art historically significant. Curators, our authoritative experts, are asked to interpret and contextualize these works through art history. Mapping the collection against time and geography, and organizing works by art historical concepts, the Timeline attracts visitors, educators, docents, students, and others who wish to understand the world, the Met, and our collection through an art historical interpretation. They come to the Timeline looking for the context and flow of history absent in individual collection records.

The Timeline, now thirteen years old, receives one and a half million visits each month, and it is the most visited section of the Met’s website. It has three hundred chronologies, one thousand essays, and more than seven thousand works of art. The Timeline is the Met’s first online publication and first attempt at creating a full picture of global art history using the Met’s collection. Its goal is to ensure that it is easy to travel through time and across cultures. The Timeline promotes high standards in academic scholarship, showcases strengths in the collection, and makes cross-cultural connections in history. The Timeline transforms curators into teachers.

Ten years into the making of the Timeline, in 2010, we began to ask questions of our efforts and of the Timeline itself:

- On the collection: Should we only care about works deemed important by historians?

- On the expert voice: Who are they? Are art historians the only experts at the Met?

- On the public: Would they want a new way to get to know the collection and the Met?

- On the institution: Are we missing out if we only present our academic side?

- On the point of view: Are there ways to engage the public emotionally?

Encounters with works of art engage, at best, the mind and the heart. Can a Web experience do the same?

3. Connections

In 2011, we launched Connections in order to give a different experience to our Web visitors. With Connections, we focused on the following points:

- On the collection: What do people like and connect with?

- On the expert voice: Are there other experts at the Met?

- On the public: What’s new? Social media.

- On the institution: What would social media do for the Met?

In place of authoritative art history, Connections asked staff to offer their personal perspectives on the Met’s vast collection, with full authorial license. The requirement for participation was simple: any staff member who had spent time working with and amongst the collections had earned the right to be a Connections contributor by sharing an interesting story, a depth of perspective, and a unique point of view. The one hundred participants included curators, photographers, conservators, publishers, educators, security guards, administrators, and many others. It was an unprecedented departure from the Met’s traditional communications strategy, which had privileged the museum director, and to a lesser degree, its curators.

The Timeline is impersonal and objective; Connections is instead personal and subjective. A visitor may encounter art historical insights in a Connections episode, but Connections is not about art history; it is about story telling, specifically one person’s story. Institutions all over (and the Met was no different) began to understand the influence of social media, technology, young visitors, and gadgets. We were not ready for the public to hijack our institution’s creativity, and yet we were interested in the directorial mandate to staff to think more broadly about general visitors and to make the museum more accessible.

We intentionally designed Connections as a one-year project (and would do so again with 82nd & Fifth). Much of the Met’s website is evergreen: the collection records and the Timeline, for instance, are iterative Web features that are built over many years, reliable resources that will also change as new scholarship and perspectives inflect the information we share with our public. With Connections, we wanted to create a feature that would be about 2011, reflecting not just the technology and tools we had at our disposal in creating the Web feature, but also the interests and enthusiasms of our content creators at that moment in time. By giving the project an end date, the museum administration was willing to provide the staff and institutional resources to really make a splash with one hundred episodes.

As we looked across the Web at what other museums have done to engage their audiences, many creative and engaging videos and Web features can be found, but for the most part these are one-offs, or perhaps part of a series of five or ten episodes. We knew that our visitors had been conditioned by television programming, news media, and the Web to expect new content on a regular basis, so we tapped into that appetite by creating Web features that would present two new episodes every week. This gave us one hundred opportunities over the course of the year to enlist new subscribers and one hundred opportunities to encourage users to share favorite episodes, so our production schedule was also our most potent marketing strategy.

Here are the ground rules for Connections. We invited one hundred diverse staff over the course of 2011 to offer personal perspectives on works of art in the Met’s collection. Each episode would be four minutes. Their voices would be personal and would touch upon any number of themes and concepts, as long as they were not art historical. The topics speak to the interests—and often the obsessions—of the participants: “Smoke,” “Tennessee,” “Bad Hair,” “Small Things,” “Birding,” “Intimacy,” “The Ideal Man,” “Dark Energy,” “Survival,” or “The Nose.”

Unlike the Timeline, we only asked for four minutes of a visitor’s time at each visit. We posted two episodes every Wednesday at 10:30 a.m. Each Connections’ episode is personal, intimate, and profound at the same time.

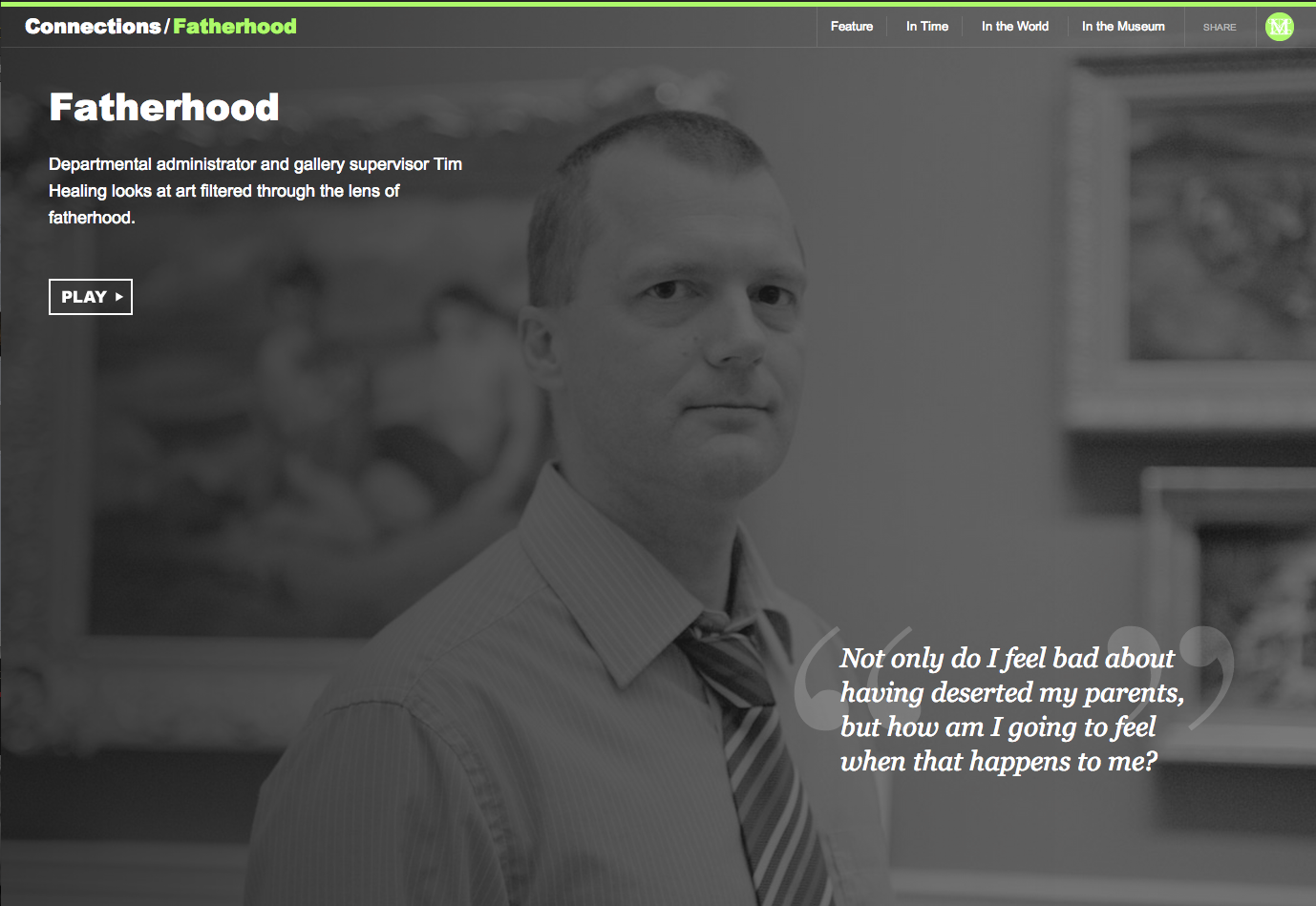

In “Fatherhood,” by Tim Healing, the departmental administrator and gallery supervisor takes the visitor through fifteen works of art. He describes:

My name is Tim Healing. I work in the department of Ancient Near Eastern Art as an administrator and gallery supervisor, and my topic today is Fatherhood.

I’ve always had an interesting relationship with my father. He was a very stern man in some ways, but quite an enigma. He was very playful at other times. And it wasn’t really until I became a father that I actually started to understand why he was like he was.

His whole thing was about support and how to support his family, how to protect his family. And his life became just those things. He’s in his seventies now, and in many ways he’s never really changed at all over that time.

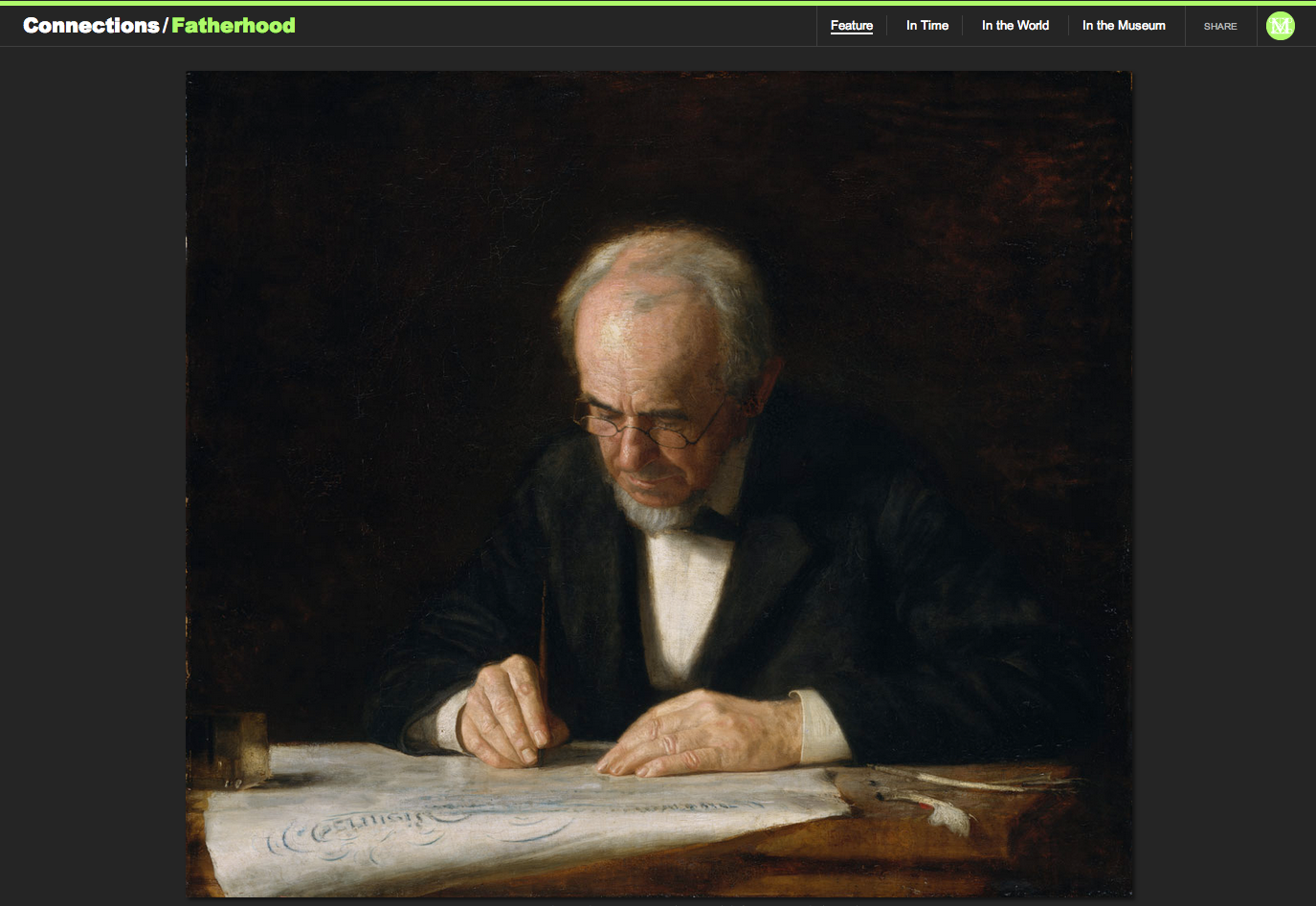

I’ve never seen him read a book, but he would always have a newspaper with him. He still does. One of the great joys of his life is to sit and read a newspaper. And he would always be sitting there reading the newspaper, but keeping an eye on us, much like the father in Reading the News in the Weavers’ Cottage. He was there to just make sure everything didn’t go completely awry.

I always wanted to be there with him, whether he was working, whether he was in the yard. I always liked to listen to his stories and things like that. I love this picture because I see the son is feeling in very much the same way. He’s leaning across the bales of fur. He’s listening to his father. I imagine they’ve been in a conversation.

He’s someone I can rely on totally for a brutally honest opinion, but I love the fact that he’s also very compassionate in a very sort of Protestant, hands-off sort of way.

I haven’t been near my parents for a great period of time. It’s sad because I look at this picture and I see the parents sitting together but in their own thoughts, with a picture of their child on the piano behind them and the grandchild as well. Not only do I feel bad about having deserted my parents, how am I going to feel what that happens to me?

The Natchez by Delacroix captures one of the most emotional times in my life. It’s a very sad picture because the Native Americans’ tribe has been massacred, but there’s been this overwhelming sense of joy as the child has been born. When this happened for me, it was this huge feeling of humility, and suddenly, the world wasn’t about my wife and myself anymore.

My daughter and my son have very different characters. It shocks me because same parents, they’re not that much age difference, but like chalk and cheese. My daughter, who’s the elder, loves to be carried. She always, if we’re out for a walk, she’ll stop, put her arms up and say, “Daddy, carry me.”

My son marches purposefully ahead and occasionally looks around to make sure you’re following. In the holiday visit to Chinatown, I see the father’s very sensitively carrying his daughter in his arms and the son is just marching away. It doesn’t even really matter if they are following.

When my children are happy, they jump up and down in a way that sometimes as adults we forget how to do. This picture just sums up every emotion for me, the joy of seeing your kids happy.

We’ve never had a family photograph without at least one child looking the wrong way. I only have two children to keep an eye on, and I always have the utmost respect for any parent, but a father of five children, it’s astonishing.

As soon as I became a father or even knew that I was going to be a father, I started to look at art and everything in a completely different way.

In the past, I would have just looked at the picture and thought, “That’s a nice painting.” Now I feel almost like an ownership, that I get a sense of what the artist really was looking for and what he meant.

Particularly, the father in the Walker Evans’ photo when he’s with his daughter, sitting on the porch. It’s just this amazing sense of closeness that there is between them. It’s just the two of them against the world. And it’s not quite as dramatic as that with my children, but I do suddenly find myself reading into things a lot.

In the beginning and throughout production, Connections made participants nervous. The Met had never asked of its staff to be this personal, to be heard, to be seen, on this scale, and online. In the recording and editorial process, we wanted our colleagues to sound authentic: intelligent, informed, thoughtful, funny, provocative, brave for doing this, and also vulnerable. The interviews were unscripted.

Once the speakers had selected the works of art that addressed their themes, they were often surprised to learn that there was nothing to prepare, no information to memorize. What they had to share about these works of art was their story, so they did not need any notes. They were speaking their own truth.

As edited for the videos, sometimes the contributors spoke about a specific work of art in detail, but very often the work of art is used to illustrate or evoke an idea they were discussing. The episodes require both text and image to be appreciated. A new kind of art historical perspective emerged as the participants considered works of art through the filter of their own experience. Speaking about “Grief” for her Connections episode after losing both her parents in the previous year, curator Andrea Bayer says about Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Socrates (1787):

How many of us have been huddled around hospital beds, sitting side by side with someone in palliative care, and the doctors have said, “This is a matter of time, there is no more that we can do.” All of these things are positions of grief that you can witness any day in a hospital. Head in hands, slumped over, some are introspective, some are out there throwing their arms up: the premonition of death and the grief to come.

Listening to Bayer, the viewers emerge with a new perspective on David’s work, and, perhaps, they connect it more viscerally to experience and their own emotional life.

Connections involved one hundred staff contributors, with curators making up one third of the group. We hoped Connections would build new audiences who were looking to the collection to speak to them poetically or inspirationally. We certainly hoped it would also enrich the experience of existing audiences—those who already trust the Met but were intrigued to encounter Met experts and others exploring the collection in new ways.

Our goal was to change the public’s relationship with the Met, and, leading by example, we wished to suggest that there are many paths through the collections. While the Timeline identified seven thousand works of art deemed art historically important, and art historians could explain their value, Connections brought out two thousand works of art that resonated with one hundred of our colleagues from all corners of the museum. To date, Connections has received two million visits.

At the closing of Connections, a one-year experiment, we began to imagine the next project. We wanted the new project to have an equally strong point of view; complement the Timeline and Connections; show a different side of the Met’s collection, the Met’s experts, and the Met’s public; and transform the Met in a different way. We wanted it to be equally powerful.

We began to ask questions of the Timeline anew, and also of Connections:

- On the collection: Works were discussed thematically on both the Timeline and Connections. Should we focus on the individual work of art?

- On the expert voice: Should we return to the curatorial voice, but this time should we ask something differently from curators?

- On the public: How would they like to engage with a work of art in the presence of the expert?

- On the institution: What can we do to transform the institution’s authoritative voice?

4. 82nd & Fifth

82nd & Fifth, named after the museum’s address at 82nd Street and Fifth Avenue in New York City, launched in 2013. We wanted to create a feature that was about an experience only to be had at the Met—in this case online—and we wanted to take advantage of the online space to present more than what a visitor could see in the gallery. With this in mind, we engaged the museum’s eleven photographers in a completely new way, giving them license to freely and imaginatively interpret the curatorial messages with photo essays.

We returned to the authoritative curatorial voice traditionally associated with the museum, but the feature challenged the curators to reflect on a work of art with which he or she has an intense intellectual connection and an equally intense emotional connection. Each curator had to make the case that encountering a work of art can be transformational. The curator would interpret the work of art, and the photographer would interpret the curator.

So the project was born: one hundred works of art, the one hundred curators they inspired, two minutes at a time. Like Connections, episodes were released every Wednesday, and they were also unscripted.

Guidelines for 82nd & Fifth helped shape each curator’s approach in presenting a work of art: the series was not about creating a Met canon, nor about museum highlights; curators should not give art history lectures, and they could not reference comparative works. When exploring a single work of art, the approach would be conversational, as if they were telling a new friend about an interesting insight the work of art had revealed to them. We would challenge our curators to tell us something that only they could say, that they would not be just reading off a script handed to them. The goal was not to situate the work art historically, but to make the case for how it transformed the curator’s perspective (and, we hope, will transform the viewer’s perspective).

In “Winners and Losers” by Xavier Salomon, a curator of Italian and Spanish painting describes Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s The Triumph of Marius (1729):

This is a painting that I walk in front of every day. As soon as I enter into the museum, I see it down the Great Hall. As I go up, the figure of Marius in his chariot starts emerging from the staircase. And it’s only once I get to the end of the staircase that I suddenly realize that there is this huge group of people towering over me. It’s very melodramatic and operatic. It’s as if the curtain has just lifted on the scene and this is all happening on a stage.

This scene is set in ancient Rome. I am originally from Rome. I grew up there. Here is this piece of my past in front of me as I’m going to work. Every time the Romans won a war, they would have a huge triumphal procession. In this case it is the victory of the war between the Romans and the Numidians. There are people rejoicing. There are captives. There are people carrying vases and sculptures and various idols that have been taken away from Numidia.

Jugurtha was the king of the Numidians. He’s there in chains. He’s in armor. He’s wearing this incredible red drapery. And I like to think of Tiepolo here as being an opera director, trying to place his characters within this scene. In opera, someone that wears red is always the person you’re going to notice first.

The picture should be all about Marius, about the fact that he did win the war, but there isn’t just one story that’s told here. The inscription at the top of the painting reads: “And the people of Rome behold Jugurtha laden with chains.” So suddenly the scene becomes not so much about the winner, but about the loser. And this is the same in a film or in a book, where your feeling about different characters changes and shifts. I tend to sometimes sympathize more with the complex personality of the bad character.

Tiepolo’s style—and the same is true for opera—is that more is more. I find it personally a very good thing. Even if you don’t like opera, you must understand that behind this huge theatrical depiction are very basic emotions that we all experience. And of course it’s the way those emotions are dressed up.

When I see this picture, I have to forget about everything that’s happening around it and just focus on the basic. There is a story about how all of us win and lose at some points in our lives and how we do that. Jugurtha is winning in this incredible dignity. It’s capturing that subtlety in life. Besides the typical historical narrative, it relates ultimately to our lives and our feelings.

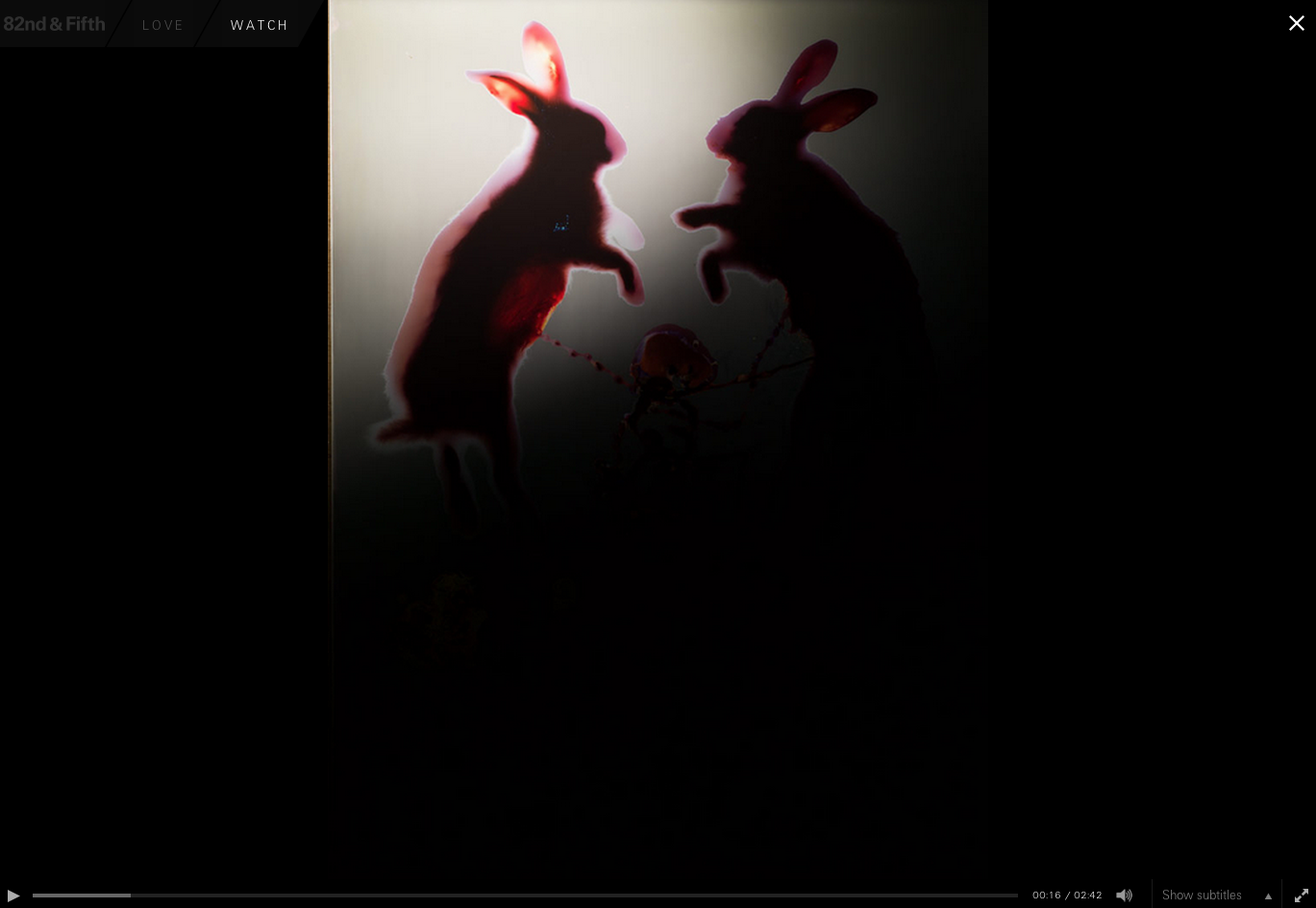

In “Love” by Mia Fineman, a curator of photography describes Adam Fuss’ Love (1992):

The artist had to create this picture in complete darkness. It’s a photogram, the earliest photographic process. He’s fumbling in the dark; that’s exactly what we do when we fall in love.

He bought rabbits from a farmer who raised rabbits for meat. He brought them home and very carefully removed their guts. He laid out a huge sheet of color photographic paper, and then in the dark placed the rabbits onto the paper.

He was doing this purely by touch. Then he exposed them to a quick, bright flash of light. It was only at the very end of the process, when he unrolled the developed paper, that he saw, for the first time, what he had created.

And there’s something so magical about this. You get sensual explosion of color. And it’s something that you can’t completely control and you can’t completely predict.

When he made this piece, the artist, Adam Fuss, was going through a period of romantic turmoil. He’s using this very traditional symbolism of fertility, of innocence and sacrifice.

It’s a picture about love and the things that happen to us when we open ourselves up and become literally entangled with another person. It’s an emblem of suffering. When you are truly in love and then you lose it, you feel like you’re being emptied out, like you’re being eviscerated, and that’s the feeling that he captures in this image.

The photogram process is like love: not knowing where you’re headed or what your ultimate connection is going to be, and then having it revealed to you in a bright, sudden flash. That’s what a great work of art does: it turns this mass of feelings into a concrete, visible form that can speak directly to each individual looking at it.

The photography in 82nd & Fifth added enormously to the success of the project. The museum’s eleven staff photographers were given an opportunity to show not three or five views of an object, but fifty to one hundred views. In the Met’s website, as in its catalogues and other publications, the photography is of a very high quality, but it can be clinical. 82nd & Fifth offered the photographers an opportunity to interpret the works of art and shoot them both in the galleries and in a studio setting. In this way, the project photography focused the eye and reshaped perception, and unlike the disembodied images in the Met’s collection database, it conveyed scale and context. It was an immersive experience that encouraged viewers to step away from the distractions of everyday life, if only for a few minutes, and steal away into the world of the object.

The goal of 82nd & Fifth was to encourage the visitor to have what John Dewey characterized as “an experience” with a work of art (Burnham & Kai-Kee, 2011). The episodes strove to give the viewer feelings of enjoyment and fulfillment, but also intense, focused seeing that would take them outside ordinary experience. The fact that the messages are educational in a grand sense is implied. We believe the ideal pedagogical approach in gallery teaching is one that is conversational—as both Connections and 82nd & Fifth are—but it is also one that creates a space and time for contemplation. With that in mind, in addition to the curatorial narrative segments titled “Watch,” we created a secondary, un-narrated segment called “Explore,” in which the visitor could continue to experience the object on his or her own, through one of various methods: 360- or 180-degree photography, site photography, closeups, archival video or audio footage, page turning, and image juxtapositions. Realizing that most casual visitors to museums spend only a few seconds with each object on view, “Explore” allowed us to lengthen and personalize the viewer’s engagement with a work of art.

82nd & Fifth‘s popularity is a match for that for Connections. Increasing awareness of our global audience, those who understand English, and those who either do not or who would appreciate our reaching out to them in their own languages, we created subtitles for all the curatorial narratives in English and in eleven languages: Arabic, Chinese (simplified), Chinese (traditional), French, German, Japanese, Italian, Korean, Portuguese, Spanish, and Russian.

5. Conclusion

While both Connections and 82nd & Fifth celebrate the collection housed within the Met, the demands of the digital space imposed an imperative on the project producers and contributors. We had to create content for not only a global audience, but also visitors who can visit The Metropolitan Museum of Art in person. By broadening the museum’s target audience, as well as who could embody the brand of the museum, the process also reshaped the institution internally.

From inside the Met, the participants had to step out of their comfort zone, overcome barriers, and address fear, relevance, narrative strategies, and trust. The Met had never asked its staff to be this personal, on this scale and online. With full support from the director, the digital space allowed the staff to be the Met’s ambassadors, and it shifted the identity and brand of the museum through a new type of engagement with our public.

Driven by storytelling, the staff came to appreciate (and our audiences experienced) a plethora of inspired, thoughtful voices and points of view. The fact that we engaged the director and over one hundred and fifty Metropolitan Museum staff members in the creation of each of these series is significant. Many of the ambitious Web or multimedia projects that museums are undertaking are largely overseen by museum staff, but executed by outside contractors. They can be very successful at modifying a museum’s profile and relationship with the public, but it can be an alienating experience for a museum staff that was largely excluded from the process of reshaping the museum’s public identity. By engaging literally hundreds of Met staff in the conception and creation of these two projects, more staff members have become committed to creating a museum that engages not just the six million visitors who enter the building, but also the millions more who visit the website.

Our public and our colleagues have told us, and we also strongly believe ourselves, that these projects have been and are very good for the soul of the museum. Within the staff of the museum, we now know we have curators who think like educators, educators who think like producers, editors who tell stories like film directors, and photographers, especially in 82nd & Fifth, who have a curator’s eye.

In this way, the public is just one quarter of the formula, if we consider the other parts to be the role of the collection, the role of the expert, and the transformation within the museum. If we do it right, all participants come to have a strong sense of ownership, everyone is willing to take a chance on behalf of the institution, and in turn we ask our public to take a chance on us.

As much as both projects have enjoyed popularity with our public, we instead measure and appreciate progress not by numbers, but by how and if the Met has become transformed even for a moment, and if our public follows. With Connections and 82nd & Fifth, viewing individual episodes is a very intimate experience. Viewed as a series, especially when watching each develop over the course of the year, is incredibly powerful as a picture of the institution at a moment in time.

The goals keep changing: online initiatives can no longer be solely about getting people into the museum. Is it about giving Web visitors authoritative facts? Is it about inspiring those with a sense of curiosity? Is it about proving that art is a universal language? Is it about leading by example? Or it is another kind of engagement? We think the key is to try them all, fully recognizing the power, impact, and importance of the institution’s internal transformation along the way.

Reference

Burnham, R., & E. Kai-Kee. (2011). Teaching in the art museum: Interpretation as experience. J.P. Getty Museum: Los Angeles.

Cite as:

T. Lai and C. Noey, Embodying the Museum: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Connections and 82nd & Fifth. In , N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published September 27, 2013. Consulted .

https://mwa2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/embodying-the-museum-the-metropolitan-museum-of-arts-connections-and-82nd-fifth/

![Figure 15: Arnold Genthe's "[Chinatown, San Francisco]," 1900s](../../wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Fatherhood7.png)

![Figure 17: Walker Evans's "[Floyd and Lucille Burroughs on Porch, Hale County, Alabama]," 1936](../../wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Fatherhood9.png)